The Beeching Axe and Its Legacy

How Railway Cuts Shaped Britain’s Transport and Heritage Railways

Introduction

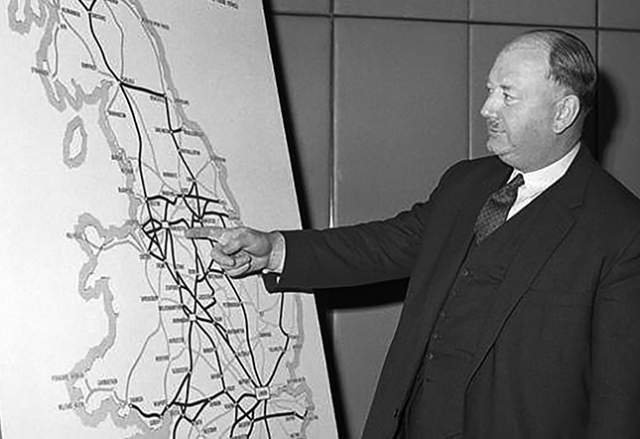

On 27 March 1963, Dr. Richard Beeching, chairman of the British Railways Board, published “The Reshaping of British Railways”—a report that would alter the UK’s transport landscape forever. Known as the “Beeching Axe,” his plan proposed closing 5,000 miles of railway lines and 2,363 stations, aiming to stem the financial losses of Britain’s nationalised rail network. While Beeching argued his reforms were necessary to modernise an inefficient system, his cuts left a lasting scar on rural communities and sparked a preservation movement that birthed today’s heritage railways.

On 27 March 1963, Dr. Richard Beeching, chairman of the British Railways Board, published “The Reshaping of British Railways”—a report that would alter the UK’s transport landscape forever. Known as the “Beeching Axe,” his plan proposed closing 5,000 miles of railway lines and 2,363 stations, aiming to stem the financial losses of Britain’s nationalised rail network. While Beeching argued his reforms were necessary to modernise an inefficient system, his cuts left a lasting scar on rural communities and sparked a preservation movement that birthed today’s heritage railways.

This blog post explores the context behind Beeching’s cuts, the immediate impact of the Beeching Axe, the rise of heritage railways, the shift from rail to road transport, and the future of rail in Britain.

The Decline of British Railways: Why Beeching Was Needed

Britain’s railway network, once the envy of the world, was a product of the Railway Mania of the 19th century. By 1914, it spanned 23,440 miles, but many lines were duplicative or unprofitable. Post-war, competition from road transport intensified. Car ownership surged from 1 in 9 households in 1960 to mass motorisation. Freight shifted to lorries, which offered door-to-door convenience. British Railways’ losses ballooned to £104 million by 1962 (£2.8 billion today).

The 1955 Modernisation Plan, which invested £1.24 billion in diesel and electric trains, failed to reverse the decline. By 1961, the railways were losing £300,000 a day.

Appointed in 1961, Beeching—a physicist and ICI executive—took a data-driven approach. He found one-third of route miles carried just 1% of passengers. Some rural lines had just nine passengers per train, covering only 10% of costs. His solution was to cut the “dead wood” and focus on profitable trunk routes. His 1963 report proposed closing 55% of stations and 30% of track, shifting freight to containerisation, and replacing rural trains with integrated bus services. The government accepted most recommendations, leading to mass closures between 1964 and 1970.

The Beeching Axe Falls: Impact and Backlash

Beeching’s cuts were brutal. Entire regions lost rail access, including the Waverley Route in Scotland, the Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway in East Anglia, and the Somerset & Dorset Line. Towns like Ripon, Leek, and Haverhill were left without trains. Scotland’s rail network shrank drastically, with only key Central Belt routes surviving.

Communities fought back. Poet John Betjeman campaigned to save rural lines. Some closures were delayed or reversed, such as the Ffestiniog Railway in Wales. But by 1970, over 4,000 miles had closed. Critics argued Beeching ignored social needs, used flawed data, and overlooked future demand.

The Birth of Heritage Railways: Saving Britain’s Railway Heritage

The Beeching cuts of the 1960s didn’t just reshape Britain’s rail network – they inadvertently gave birth to a remarkable preservation movement that has become one of the most successful heritage railway sectors in the world. What began as desperate attempts to save doomed lines has grown into a vibrant industry that attracts millions of visitors annually and keeps Britain’s railway heritage alive.

The Early Pioneers of Preservation

Even before Beeching’s axe fell, visionaries were laying the groundwork for what would become the heritage railway movement. The Talyllyn Railway in Wales became the world’s first volunteer-run preserved railway when it was saved from closure in 1951. This narrow-gauge line in Snowdonia set the template for future preservation efforts, showing that enthusiasts could successfully operate a railway.

The **Bluebell Railway** in Sussex followed in 1960, becoming the first standard gauge line to be preserved by volunteers. Its success in saving a section of the Lewes to East Grinstead line demonstrated that mainline railway preservation was possible. These early pioneers proved that with enough passion and volunteer effort, even railways deemed “unprofitable” by British Railways could have a viable future.

The Post-Beeching Preservation Boom

As Beeching’s cuts took effect between 1964 and 1970, railway enthusiasts across Britain mobilized to save what they could. The sudden availability of complete railway lines – with tracks, stations and infrastructure still intact but facing demolition – created unprecedented opportunities for preservation.

Some of the most significant heritage lines established in this period include:

- The Severn Valley Railway (1965): Saved a picturesque 16-mile route through Worcestershire and Shropshire that had been completely closed by British Railways.

- The North Yorkshire Moors Railway(1967): Preserved a stunning section of the Whitby-Pickering line through the North York Moors National Park.

- The Dart Valley Railway (1968): Rescued part of the former Great Western Railway branch line in Devon.

What made these early preservation efforts remarkable was their grassroots nature. They were typically started by small groups of railway enthusiasts who pooled their limited resources, often working in their spare time to restore crumbling infrastructure and rescue withdrawn steam locomotives from scrapyards.

The Evolution of Heritage Railways

From these humble beginnings, Britain’s heritage railways have grown into a sophisticated sector that combines historical preservation with tourism and education. Today’s heritage lines offer far more than just nostalgic train rides – they’ve become:

Living Museums

Many heritage railways have recreated authentic period stations and operating practices. The Keighley & Worth Valley Railway, famous as the filming location for “The Railway Children,” maintains its stations in 1950s/60s condition. The Great Central Railway operates the only preserved mainline double track in Britain, allowing authentic passing manoeuvres.

Engineering Workshop

Several railways now maintain extensive engineering facilities. The Festiniog Railway in Wales operates its own locomotive and carriage works, while the North Norfolk Railway has become a centre for vintage carriage restoration. These facilities preserve traditional engineering skills that might otherwise be lost.

Major Tourist Attractions

Heritage railways have become significant contributors to local economies:

- The North Yorkshire Moors Railway attracts over 300,000 visitors annually

- The West Somerset Railway contributes £10 million per year to the local economy

- The Strathspey Railway in Scotland supports 50 full-time equivalent jobs

Educational Resources

Many railways now offer formal education programs. The Didcot Railway Centre provides STEM education using railway engineering, while the Ravenglass & Eskdale Railway in Cumbria offers school programs about industrial history.

Challenges and Innovations

Modern heritage railways face numerous challenges, from rising insurance costs to aging volunteer bases. However, they’ve responded with innovative solutions:

Diversification

Many lines now host special events like dining trains, murder mysteries, and seasonal celebrations (such as the popular “Polar Express” Christmas trains) to boost revenue.

New Technologies

Some railways are adopting modern technologies while maintaining historical authenticity. The **Welsh Highland Railway** uses biodiesel in some locomotives, and several lines have implemented online booking systems.

Strategic Partnerships

Heritage railways increasingly collaborate with mainline operators. The Swanage Railway now runs regular services connecting with South Western Railway, while the Jacobite Steam Train (made famous by Harry Potter) operates over Network Rail tracks.

The Future of Heritage Railways

As we move further from the steam era, heritage railways face the challenge of remaining relevant. However, several trends suggest a bright future:

Growing Popularity

Visitor numbers continue to rise, with many railways reporting record attendance in recent years. The appeal seems to be broadening beyond traditional railway enthusiasts to include families and history lovers.

New Preservation Projects

Ambitious new projects continue to emerge. The Stainmore Railway Company aims to reopen a 12-mile section of the former South Durham & Lancashire Union Railway, while the Colne Valley Railway in Essex is extending its running line.

Mainline Steam Operations

The success of mainline steam tours (operated by companies like the Railway Touring Company and West Coast Railways) demonstrates ongoing public appetite for heritage rail experiences on the national network.

The heritage railway movement born from Beeching’s cuts has become one of Britain’s most successful cultural preservation stories. These railways don’t just preserve the past – they continue to evolve, finding new ways to keep Britain’s railway heritage alive for future generations. Their success stands as a powerful testament to what can be achieved when passion meets preservation.

The Shift from Rail to Road: Did Beeching’s Plan Work?

The Beeching Report didn’t just cut railways—it accelerated Britain’s transformation into a road-centric society. This seismic shift reshaped the economy, environment, and daily life in ways Beeching only partially anticipated.

The Road Revolution: Policy, Investment, and Cultural Change

In the post-war years, Britain underwent a radical transformation in how it moved people and goods, and few figures were more central to this shift than Dr. Richard Beeching. While often remembered for his role in cutting thousands of miles from the rail network, Beeching’s actions were part of a much larger movement: a national pivot towards road transport, backed by powerful policy decisions, heavy investment, and a deep cultural shift.

The government’s intentions were clear. The 1959 Motorway Act kick-started the construction of a 1,000-mile motorway network, and between 1958 and 1964, public spending on roads tripled. Rail investment, by contrast, remained stagnant. This wasn’t just about infrastructure—it was a sign of changing priorities.

The car soon became king. Car ownership exploded, rising from just 2 million vehicles in 1950 to 11 million by 1970. By the mid-1970s, over half of UK households owned a car, up from just 14% in 1951. Cars weren’t just practical—they symbolised freedom, personal success, and modern living. New suburbs grew in tandem with expanding road networks, while out-of-town supermarkets, like Tesco’s first superstore in 1961, began to redefine how and where people shopped. Commuting patterns shifted too, with homes and jobs increasingly shaped by road access rather than rail lines.

Freight’s Transformation: From Rails to Roads

Beeching saw the writing on the wall for rail freight. Even before his reports, the sector was in decline—ton-miles transported by rail had nearly halved between 1952 and 1962. After his cuts, that collapse accelerated. By 1975, rail freight accounted for just 10% of the market, a dramatic fall from its 90% share in 1945. Roads quickly took over, especially for short- and medium-distance deliveries.

The reasons were clear. Lorries offered flexibility—no need for trans-shipment or coordination between terminals. Just door-to-door delivery, simple and fast. And it was cheap. Heavy goods vehicles only paid about 25% of the damage they caused to roads via taxation. The rest was picked up by the public purse. Meanwhile, new motorways like the M1, opened in 1959, slashed lorry journey times by up to half. It was no contest.

Environmental and Social Costs: The Uncalculated Price

Yet for all its economic logic, Beeching’s rail restructuring largely ignored the environmental and social consequences of putting nearly everything on the road.

Congestion became a chronic problem. By 2020, delays from urban traffic were costing the UK around £8 billion a year. Road transport also took a heavy toll on the environment. It became the largest source of CO₂ emissions in the country—transport now accounts for 27% of the total. Freight by road emits nearly twice as much carbon per ton-mile as rail.

Then there were the human costs. When rail lines were closed, over 500 villages lost their only reliable public transport link. For many residents—especially the elderly and those on lower incomes—this meant social isolation and reduced access to jobs, healthcare, and services. Safety was another major concern. In 1965, nearly 8,000 people died in road accidents. On the railways that same year, the figure was just 27.

Beeching’s Freight Vision: Successes and Failures

Not all of Beeching’s vision was flawed. He championed the idea of containerisation, which has since revolutionised global freight transport. The Freightliner service, launched in 1965, still forms a vital part of the UK’s logistics infrastructure today, moving an estimated £30 billion worth of goods annually. Modern intermodal hubs, like the Daventry International Rail Freight Terminal, now handle over 16 trains per day.

But Beeching also made serious missteps. His closure of 1,300 freight depots happened before the road system was truly ready to handle the volume. He also underestimated the future growth of port traffic. As containerisation boosted the fortunes of ports like Southampton and Felixstowe, the rail links they once depended on had already been severed.

In the end, the shift from rail to road was not just about transport—it was about a new vision for Britain. One rooted in car ownership, suburban life, and flexible logistics. But it came at a cost that is still being counted today, in carbon emissions, social exclusion, and congested streets.

The Rail Freight Renaissance (1990s–Present)

Though Beeching’s cuts cast a long shadow over Britain’s railways, the story didn’t end there. In the decades that followed, rail freight made a surprising comeback—driven by new market forces, political decisions, and global trends that Beeching himself could never have predicted.

Privatisation in 1993 marked a key turning point. By opening up the sector to competition, it injected a fresh wave of innovation. Operators like DB Cargo introduced electric aggregate trains and specialised logistics services, demonstrating that rail could still be modern, efficient, and competitive.

Environmental concerns also played a growing role. One freight train can take up to 76 lorries off the road, slashing carbon emissions and easing congestion. As climate targets tightened, this made rail freight increasingly attractive to both policymakers and major businesses.

Globalisation brought further opportunities. The Channel Tunnel, once seen primarily as a passenger route, evolved into a vital freight corridor. Today, it handles around 1.5 million tons of cargo annually, connecting the UK with continental Europe’s vast logistics networks.

Government strategy began to reflect this shift. The Rail Freight Strategy published in 2016 set an ambitious target: to increase freight volumes by 75% by 2036. Support for infrastructure upgrades, terminal expansion, and digital signalling has followed in fits and starts, signalling a renewed official belief in the value of rail freight.

A glance at the numbers tells a complex story of progress and persistence. Since the mid-1960s, rail passenger numbers have soared—miles travelled have more than tripled. Road use, too, has surged, with vehicle miles more than doubling.

Freight, however, tells a tale of uneven fortunes. Despite a period of decline and a modest resurgence, rail freight volumes remain slightly below their 1965 level. In contrast, heavy goods vehicle (HGV) freight has nearly tripled over the same period, showing just how dominant road haulage has become.

At the same time, the environmental cost of this road-heavy system has crept upward. CO₂ emissions from transport have risen by 18% since 1965, reflecting the sheer scale of today’s vehicle movement and the stubborn reliance on fossil fuels.

The data paints a mixed picture: while rail has staged a comeback in some areas, especially in passenger travel and strategic freight corridors, road transport still dominates. Yet the potential for rail remains—especially as climate goals, fuel costs, and congestion concerns mount. The question is whether the UK will seize this moment to rebalance its transport future, or let the momentum fade once again.

Reckoning with the Legacy: Beeching’s Unintended Consequences

As Britain looks back on its post-war transport choices, a series of unintended consequences emerge from Beeching’s era—consequences that still shape daily life, from the morning commute to national supply chains.

The first paradox is a striking one. Just as cities began to expand in the 1960s, Beeching’s axe fell hardest on the rural and suburban lines that could have supported that growth. Today, commuter services into cities like London are bursting at the seams, handling four times the passenger volumes they managed in the 1960s. The very lines once deemed unnecessary have become the arteries of Britain’s modern workforce—only now, many are gone or operating beyond capacity.

Then there’s the logistics imbalance. In shifting so heavily toward road transport, the UK supply chain became dangerously dependent on lorries and fuel. This fragility was laid bare during the fuel protests of 2000, when just a few days of disrupted deliveries left supermarket shelves empty. Without rail as a meaningful backup, the country’s food and goods network proved alarmingly vulnerable.

And in a surprising twist, it was enthusiasts and volunteers—rather than central planners—who helped preserve a vital part of the rail legacy. Heritage railways, once seen as nostalgic curiosities, now attract around 13 million passenger journeys a year. These preserved lines aren’t just tourist attractions; they’re living evidence that local rail services dismissed as “uneconomic” continue to hold real public value.

A Road to Nowhere?

In many ways, Beeching solved the rail industry’s immediate financial problems—but at the cost of creating deeper, longer-term crises. Britain’s growing dependence on roads has brought with it chronic congestion, rising carbon emissions, and social isolation in communities left behind by rail closures.

Although rail freight is recovering, the road still carries 86% of the UK’s goods. The sheer dominance of road transport remains a major challenge for any serious attempt to build a greener, more resilient future.

The lesson is clear: transport policy must be about more than cost-cutting. It must account for resilience, environmental impact, and social equity—factors that never made it onto Beeching’s balance sheets. As the UK pushes toward net-zero by 2050, the next great transport revolution may be a reversal of the last—one that puts rail back at the heart of the nation’s infrastructure, not as a relic of the past, but as a foundation for the future.

The Future: Are Beeching’s Cuts Being Reversed?

The legacy of the Beeching Axe is no longer set in stone. A quiet revolution is underway as communities, governments, and transport planners reassess the value of severed rail connections. What began as symbolic reopenings has evolved into a strategic movement to restore critical links – yet significant barriers remain.

Reopenings Gaining Momentum

Recent years have seen tangible progress:

- Borders Railway (2015): Scotland’s £350 million revival of the Waverley Route restored 30 miles of track to Tweedbank, carrying **1.5 million passengers annually** within 5 years – triple initial projections.

- Dartmoor Line (2021): The Okehampton-Exeter link reopened after 50 years, with services hourly within months. Local ridership hit 127,000 in its first year.

- Levenmouth Rail Link (2024): Reconnecting Fife’s largest town (Leven) to Edinburgh within 60 minutes, serving 1,200 new homes and an offshore wind manufacturing hub.

- Portishead Line (2026 expected): A £152 million project restoring service to this Bristol commuter town after 60 years.

Strategic Wins Beyond Nostalgia

Modern reopenings focus on economic/environmental returns:

- Carbon Savings: Restored lines like Okehampton cut 7,000 tonnes of CO₂ yearly by diverting commuters from cars

- Housing Links: The Tavistock-Bere Alston line (planned) would serve 14,000 new Plymouth homes

- Freight Revival: Reconnecting March-Wisbech (Cambridgeshire) could carry aggregates from Norfolk quarries.

Beeching’s cuts took 5 years to implement – their partial reversal will take 50. With each mile reopened, Britain rediscovers an enduring truth: railways shape communities in ways spreadsheets can’t measure.

Conclusion: Beeching’s Complicated Legacy

Beeching was neither hero nor villain—he made tough choices for a failing industry. His cuts saved British Railways from collapse but left lasting transport gaps and inspired heritage railways that keep history alive. As the UK re-evaluates rail’s role in a green economy, Beeching’s report remains a cautionary tale about balancing efficiency with social need.